It was about 7 AM and I was sipping my coffee and glancing through that morning's Boston Globe. I was at about 700 feet, 100 miles offshore and heading slightly southeast in a Piper Super Cub. That morning, the boats were on the northeast peak, on the eastern end of George's Bank, so it was about a 220 mile flight. At 95 MPH fully loaded with fuel (I carried about eighteen hours' worth) it was about as far offshore as we ever went. I was wheels off from Plymouth at 6 AM. Below me, as far as I could see in all directions, was fog, topping out at about 400 feet. I was 300 feet above it, giving myself a decent margin in case I got absorbed in a Globe story and let my altitude drift too much. Above me was nothing but clear blue sky, and the boats said on the sideband that morning that they were in the clear, so it looked like it might be an OK day.

Suddenly the radio crackled to life. I carried five radios, and it took me a second to realize which one it was and crank the volume up in the headphones. It was Jack, who had left the Vineyard in a Citabria about the same time I left Plymouth. I knew he was still south of me, but we were on a converging course. "What's happening, Jack?" I said, and he rattled off some Loran numbers and said I had to get over there and see this. He had a half-mile hole in the fog, and there was a commotion in the ocean. He was only about six or seven miles south of me, so I turned south and ran down the Loran line. Soon I saw a little airplane circling ahead of me, and as I approached there was a gap in the fog and big splashes in the water. There was a big old grandaddy humpback, not doing well, and two smaller females trying to help him. Every time the big one rolled over, one of the smaller whales would swim around, approach from the side, and with her snout roll him back upright, while the other female stationed herself on his other side to try to keep him from rolling too far the other way. They were obviously trying to keep him upright and keep his blowhole out of the water. We saw no blood or obvious wounds, and couldn't tell what was wrong. He seemed to know that the females were trying to help, and it was an amazing and touching sight. There was nothing we could do for him, so after ten minutes or so we wished him well and continued on our way. The boats were waiting. We checked the numbers on our way home that night, twelve hours later, but found no sign of them. So I don't know what happened to him.

I grew up by the water in Cohasset, Massachusetts when we weren't traveling. My father was a doctor in the Navy, and then the foreign service. I went to kindergarten in Italy and grades 2-4 in Karachi, Pakistan. I had crossed the Atlantic, the Mediterranean, the Indian Ocean, and the Pacific by ship before I was ten, but Cohasset was always the base, and the water was always near.

Summers from age 10-18 I was on the water every spare minute I had. Rowboats, sailfish, small wood lapstrake skiffs, and a thirteen foot whaler were all part of it. In eighth grade, I built an eight foot racing hydroplane from plans in Popular Mechanics, my only other attempt at boat building. Paid for with lawn mowing money, hard chined, it wasn't very safe, but in still water with 15 HP it was enough to scare the hell out of me. From about age eight on, I told everyone I was going to build a boat.

After graduating from Brown in 1970, with a major in anthropology and a minor in metal sculpture, a friend, Steve Heller, and I drove down to Guatemala, 250 miles on a dirt road into the Peten, where we were skin divers at a Mayan temple site on a lake. Returning to Cohasset to photograph some sculpture I had done in college, I fell into making wind bells with a friend from Cohasset, Dick Fisher. With a pushcart and a peddlar's license, we sold bells on Newbury Street in Boston through the winter of '70-'71.

Throughout the '70s life was pretty good. By the end I was selling bells in all fifty states, and employed five high school kids from the alternative program at the local high school. I was also doing some pretty large metal sculpture in the winters of those years, with some success.

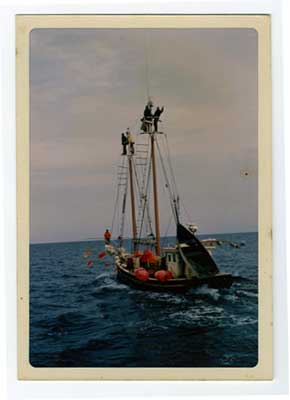

I started commercial swordfishing, out of Scituate, in the summer of 1971. I made a couple of two week trips a summer, because I found it fascinating, and the money was great. At that time no one was long-lining; we took seventy foot boats 200 miles out to the eastern end of George's Bank, and would spend 2-3 weeks out there. Laying to at night, the boats had sixty foot top masts, with a throttle and wheel and radio up there, and a 25 foot aluminum stand on the bow from which the harpoon was thrown. We used an airplane (a highly modified Piper Super Cub) to spot the fish and guide us to the spot. Exciting doesn't begin to describe it. We saw lots of life, and all kinds of weather. We stayed out in anything less than fifty knots, especially if we didn't have a trip yet. Occasionally we got caught, and would run to Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, to duck the weather.

I

soon graduated to flying the airplane, which was great fun and got me home

at night. We flew horrendous, unbelievable hours— my record was 86 hours in

the air in six days— but it always came to an end, we got some sleep, and

did it again. I saw large amounts of ocean, weather, and oceanic life in a

concentrated time. With 3500 hours of fish spotting, I've covered some 250,000

miles of ocean from 500 feet. I also made countless 2-3 week trips to George's

Bank in the boat, as alternate captain while the owner flew the airplane and

I threw the harpoon, and later, about eight 35 day longline trips to the Grand

Banks in October and November, 1200 miles offshore. It took us 5 days and

nights just to get there. So I've seen a lot of water.

I

soon graduated to flying the airplane, which was great fun and got me home

at night. We flew horrendous, unbelievable hours— my record was 86 hours in

the air in six days— but it always came to an end, we got some sleep, and

did it again. I saw large amounts of ocean, weather, and oceanic life in a

concentrated time. With 3500 hours of fish spotting, I've covered some 250,000

miles of ocean from 500 feet. I also made countless 2-3 week trips to George's

Bank in the boat, as alternate captain while the owner flew the airplane and

I threw the harpoon, and later, about eight 35 day longline trips to the Grand

Banks in October and November, 1200 miles offshore. It took us 5 days and

nights just to get there. So I've seen a lot of water.

Throughout the '70s, I also sailed whenever I could. My old roommate from college, Nick Litchfield, and his wife Nancy circumnavigated from 1974-1978, and I cruised Maine extensively with them, and also spent a month in the Bahamas.

By the end of the '70s, I was ready to build a boat.

I spent my thirtieth birthday single, flat on my back, in bed with a cast on my right leg up to my waist. It was a bad skiing break, and life wasn't really looking too good.

Since I was about eight years old I had wanted to build a boat, and looking back over my life to that point in time I decided that this was the time to get started.

I spent the eight months in the cast refining what I wanted incorporated into my ideal boat, and came up with a 15-page single-spaced type-written list of design requirements. I shopped this list to half a dozen design firms, and finally settled on Ted Brewer because he seemed to have the most experience at that time designing round, or radius chined, metal boats. I did want steel, from my commercial fishing years, and I didn't want a hard chine, either single or double. Over the course of about six months, Ted came up with around a dozen drawings, and construction started in April of 1979.